Conservation is a term that is often used in psychology to describe the understanding that certain physical characteristics of objects remain constant, even when their appearance changes. It’s a fundamental concept in the field of cognitive development, first introduced by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget in the 1920s.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that children go through distinct stages of cognitive growth, each characterized by a unique set of abilities and limitations. Conservation is considered to be a key milestone in this development, as it marks the transition from a preoperational stage to a concrete operational stage. Understanding conservation requires children to be able to mentally manipulate and transform objects in their minds, a task that becomes increasingly complex as they grow older. In this article, we’ll explore what conservation is and why it’s important in the study of psychology.

Conservation Tasks

Conservation tasks are experimental tasks designed to assess children’s understanding of conservation. These tasks typically involve presenting children with two identical objects that are then manipulated in some way, such as by pouring the contents of one container into a different-shaped container. The child is then asked whether the two objects are still the same or whether one has changed in some way.

Liquid Conservation Task

One of the classic conservation tasks is the conservation of liquid task, which involves pouring the same amount of liquid from one container into two different-shaped containers. Young children in the preoperational stage tend to focus on the superficial characteristics of the containers, such as their size or shape, rather than the amount of liquid they contain. As a result, they may believe that the container that appears larger actually contains more liquid. However, as children progress into the concrete operational stage, they begin to understand that the amount of liquid remains the same, regardless of the container’s shape or size.

Number Conservation Task

The conservation of number task involves presenting children with two rows of objects that are then spread out or brought closer together. Children in the preoperational stage tend to focus on the physical arrangement of the objects, rather than the number of objects in each row. As a result, they may believe that the row with more spread-out objects contains more objects, even though the number of objects in each row is the same. However, as children progress into the concrete operational stage, they begin to understand that the number of objects remains the same, regardless of their physical arrangement.

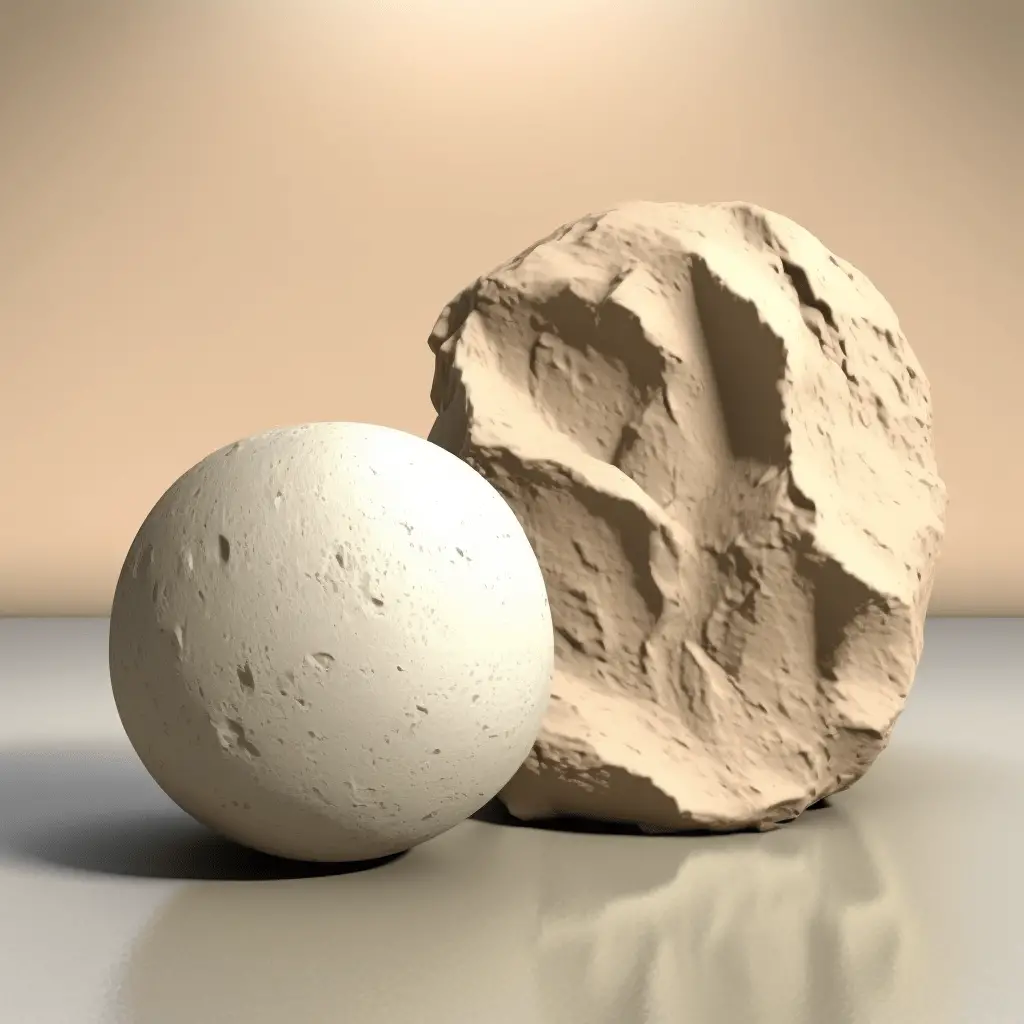

Solid Quantity Conservation Task

The conservation of solid quantity task involves presenting children with two identical objects that are then manipulated in some way, such as by flattening one object into a wider shape. Children in the preoperational stage tend to focus on the physical appearance of the objects, rather than their volume or quantity. As a result, they may believe that the flattened object now contains more material, even though its volume remains the same. However, as children progress into the concrete operational stage, they begin to understand that the amount of material remains constant, regardless of the object’s shape.

Weight/Mass Conservation Task

The conservation of weight/mass task involves presenting children with two identical objects that are then manipulated in some way, such as by spreading a clay ball into a flatter shape. Children in the preoperational stage tend to focus on the visual appearance of the objects, rather than their weight or mass. As a result, they may believe that the flatter object now weighs less, even though its mass remains the same. However, as children progress into the concrete operational stage, they begin to understand that weight is not a reliable indicator of mass and that the amount of material in each object remains constant.

Ages and Conservation Tasks in Psychology

When it comes to completing conservation tasks, there’s no one-size-fits-all age range. Some kids might pick it up earlier, some might take a little longer. Plus, different countries might have different ages for when kids start to get it (check out conservation across cultures for more on that!). But generally, most kids start to get the conservation of number task right around ages 6-8, while the conservation of mass and length kicks in around age 7. Kids might not get the hang of the conservation of weight until they’re around 9 years old, and the conservation of volume? That might not click until they’re 11!

Now, Piaget did some serious studying on conservation and figured out that there are different stages kids go through to get the hang of it. In the first stage, they just can’t quite get it – during the conservation of liquid task, they might think a taller glass has more liquid just because it’s taller! In the second stage, kids start to use width as a reason too, so they might say a shorter, stouter glass has more liquid than a tall, skinny one. But in the third stage, they finally get it and understand that height and width don’t affect the amount of liquid.

What’s interesting is that kids who have developed the ability to conserve really believe in their answers and are more likely to manipulate the materials to prove their point than kids who haven’t gotten the hang of it yet. But here’s the good news: training tasks can help kids who haven’t quite grasped conservation yet to get there. Even four-year-olds can start to learn using operant training, which just means they repeat the tasks and get reinforcement for correct answers while getting corrected for incorrect ones. And get this – once they start to get the hang of one conservation task, that success can transfer to other conservation tasks too!

Criticism of Conservation Tasks

Some researchers have criticized the conservation tasks and Piaget’s theory on the research methods used. Many studies have looked at variations of the conservation tasks and how these variations affect children’s responses. Researchers found that children need to be assessed both verbally and non-verbally, as assessing them only in a verbal manner can sometimes result in inaccurate test results that suggest some children are unable to conserve. In reality, some children are only able to answer conservation tasks correctly in a non-verbal manner.

Research has also suggested that asking the same question twice may lead young children to change their answer, assuming they were wrong the first time around. And the importance of context was emphasized by some researchers who altered the task so that a ‘naughty teddy’ changed the array rather than an experimenter themselves. This change seemed to give children a clear reason for the second question being asked, and four-year-old children were able to demonstrate knowledge of the conservation of matter much earlier than Piaget’s reported 7- to 11-year-old threshold for concrete operations.