Born in the small Bavarian town of Kallstadt, modern-day Germany, Friedrich was the son of Christian and Katharina. Kallstadt at the time was a land known for viticulture, the caring for and harvesting of grapes destined for vineyards. But caring for grapes isn’t as blissful as the end-product tastes.

It’s long hours, hard work, and grueling backaches if you do it for too long.

And our little Bavarian friend was unfortunately quite sickly and weak in his younger years.

His mother even refused to let him work the fields alongside the rest of the family. Instead, she chose to have him train as a barber’s apprentice in a nearby city.

Rewind about 15 years before this hairy adventure and Bavaria had become enveloped by the newfound German Empire. And this Empire wasn’t exactly famous for being peaceful, as I’m sure you know.

The country also required mandatory military conscription from all of its loyal 18-year-old male subjects for many years.

And our young 16-year-old barber’s apprentice wasn’t very loyal at all.

America Bound

Young Friedrich was terrified of joining the army. Three years of brutal discipline imposed on any young man by the Prussian armed forces was enough to turnover anyone’s insides — especially if you were of a sickly disposition.

So, Fred fled in the middle of the night, leaving nothing but a note and abandoning his family.

“I agreed with my mother that I should go to America.” — Friedrich to a friend later in life

He made his way slowly to the West, a land of opportunity and an escape from the politics of Europe, at least at the time.

Abandoning your civic duties was dealt with a bit differently back then though. No prison time awaited young Friedrich if he returned. He simply couldn’t return.

A royal decree was issued, banning him from the country.

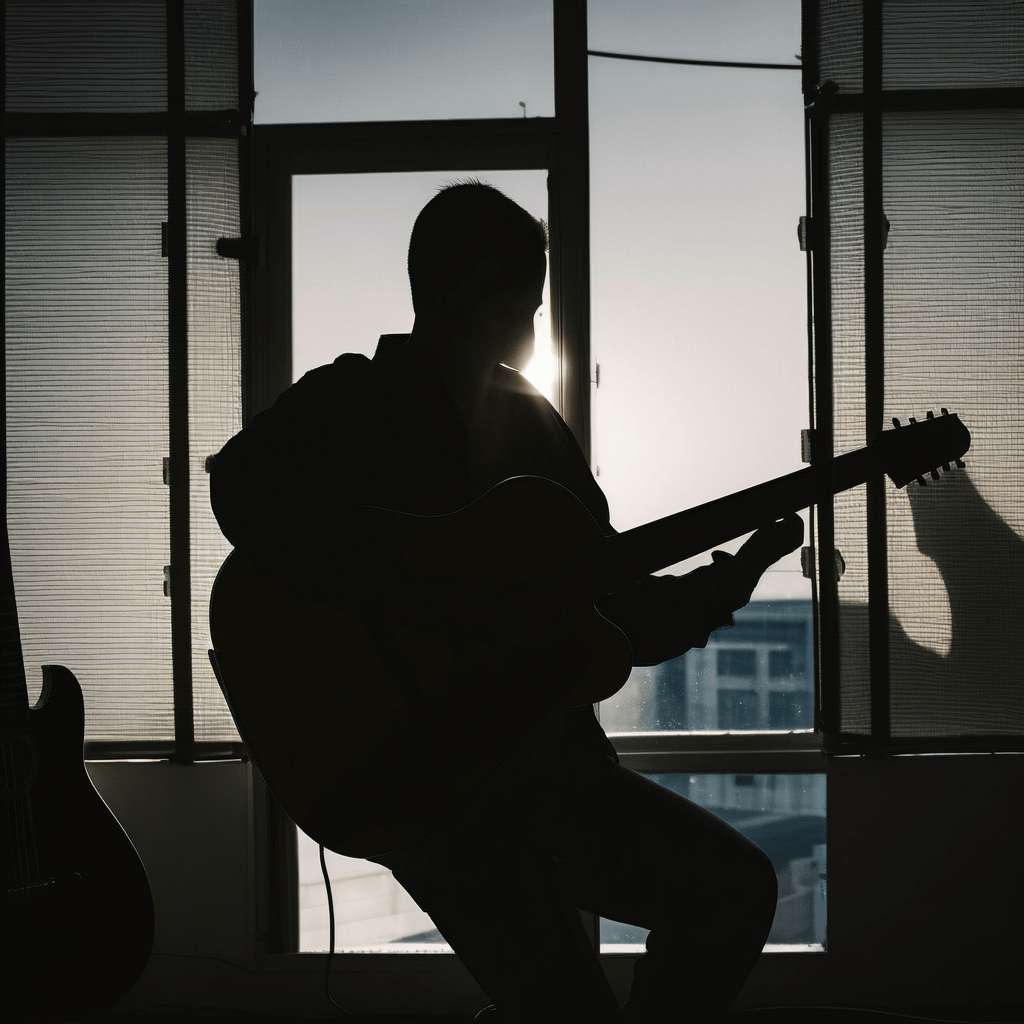

On October 16 of 1885, sickly Friedrich arrived aboard the SS Eider oceanliner at New York’s Emigrant Landing Depot. Performing an illegal emigration from Germany, at least under their law of conscription.

New York, New York

He settled in quickly.

He moved in with his older sister who had moved to New York a few years earlier. By luck, he met a fellow German barber who needed help on the very first day. He ended up assisting that man for the next 6 years.

But our young Friedrich had bigger ambitions. By this point, he had saved up several hundred dollars, around $10,000 in today’s currency.

He looked to the West coast and its relative freshness compared to the overcrowded East coast. Specifically, he wanted to move to Seattle.

A city that was only 40 years old by then and in the brand new state of Washington.

Eager to set his mark on the world, Friedrich moved there and purchased a struggling business called the ‘Poodle Dog.’

The restaurant was smack dab in the middle of the infamous Pioneer Square. An incubator of gambling dens, saloons, seedy hotels, and brothels.

The restaurant itself was pretty plain. Friedrich immediately renamed it the ‘Dairy Restaurant’ and sold food, liquor, and “Rooms for Ladies.”

“Rooms for Ladies,” in 1891 speak, meant hookers.

Golden Eyes

In 1894, Friedrich sold off his ‘dairy’ restaurant and moved to an exciting little town by the name of Monte Cristo, also in Washington.

Gold was recently discovered in ‘dem ‘der hills and Fred wanted his little hands on some of it.

And so, our enterprising young German friend now embarked on his second illegal action after prostitution.

He wanted to buy a strip of land near the train station in Monte Cristo.

If it truly was about to be booming, as the rumors were saying, surely all of the new gold diggers would need a place to stay — and maybe some rooms for ladies too.

But he couldn’t afford the land.

However, he found out he could file a gold placer claim, at least to reserve the plot.

Back then, a simple gold placer claim was cheap and allowed an individual the rights to the minerals below the ground. It didn’t, however, allow a person to build a hotel or other physical building.

But hey, corruption was in full swing back then, and the local officials turned a blind eye.

Little Friedrich wasn’t even the first claimer of the mineral rights there. He made the 2nd claim on the same plot of land and used some convincing to have the local officials ignore the 1st claim.

Tsk, tsk, young Friedrich.

He had enough money to buy some lumber and hire a few hands to build a small hotel. And even though he didn’t have the legal authority to build it, the service was in such demand that people continued to ignore his dancing on American legalities.

After less than a year, he was able to purchase the full rights to the land. This was despite the rival placer claim owner filing a lawsuit and trying to collect rent.

But apparently, by this point, the locals appreciated Fred’s services so much they simply chose to ignore the action. They appreciated his illegal services so much that they even elected him as a justice of the peace two years later!

But alas, Monte Cristo was full of too much hype, and by 1896, most people had started leaving the town due to a lack of actual gold in ‘dem ‘der hills.

This was no matter for Friedrich— he had made his money from the miners, not the gold.

To the North

Before withdrawing completely from Monte Cristo, Friedrich had started laying some bets down.

He had recently met two miners who were just about to travel North to the famous Klondike Gold Rush.

In exchange for a small piece of their potential winnings and for them to stake claims for Friedrich himself, he fully funded their expedition.

At the same time, he opened up a new restaurant back in Seattle, using his Monte Cristo funds to create a booming business there.

Friedrich got a taste of the lucrative mining life in Monte Cristo. He realized something most people didn’t. While thousands of wannabe-rich folk were flocking to mining claims all around North America, Friedrich realized most of them left penniless or worse.

Mining the miners was the real way to earn.

And Fred certainly knew this.

He sold all of his properties in Monte Cristo, collected a huge amount of supplies, and headed north to the Yukon to go repeat his new business model at a much grander scale.

The Klondike

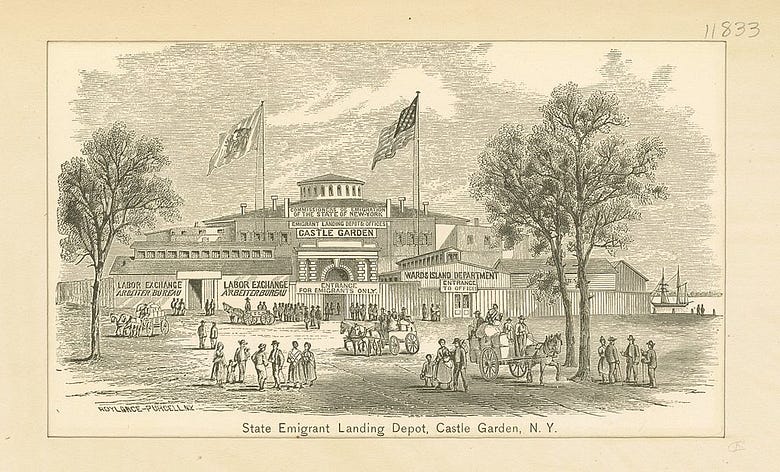

After an arduous journey that would’ve taken months to complete, Friedrich had befriended a miner named Ernest Levin. In 1898, they opened a small tent restaurant along the extremely dangerous Dead Horse Trail, a part of the White Pass route.

As you may have guessed, the path was called ‘Dead Horse Trail’ because miners abused their animals so much the trail was littered with corpses of the poor animals. They were left as they lay, often taking extremely long times to decompose in the frigid cold.

The main dish at Friedrich’s restaurant?

“Fresh-slaughtered, quick-frozen horse.”

Yummy.

Friedrich and his new business partner soon departed the horse restaurant for a nearby town called Bennet, in British Columbia, Canada. This town was a key stopover for would-be miners making their way up to the Klondike.

At first, they opened a tent restaurant and called it ‘The Arctic.’ Heavy demand soon led them to create a proper two-story building that offered lodging, liquor, food — and you guessed it — rooms for ladies.

In 1900, the major railroad joining up Whitehorse and Skagway had been completed. Anyone looking to make their fortune in the Yukon now had a much safer way to travel — and a mandatory stop in Whitehorse.

Always one to follow a trend, Friedrich literally had his two-story hotel uprooted and hauled by boat up to Whitehorse.

He renamed it — The White Horse. How original.

They soon likely expanded the size of the building, as they were noted as serving up to 3,000 meals per day. The business now also offered gambling in addition to just rooms for ladies and other features.

More Money, More Problems

Business was good. Thousands of customers. Authorities paying a blind eye to all of the ill-gotten gains as long as Fred and his business partner behaved.

This continued for almost two years until problems arose, as they always do in these stories.

Ernest slowly developed a particularly nasty drinking habit. The local authorities also were growing tired of the ill-repute of the city and one day declared prostitution, gambling, and liquor illegal.

While they had one year before the crackdown would be enacted, Friedrich had seen something like this before in Monte Cristo. Soon after, he sold his entire share to Ernest and departed the city.

Within a year, Ernest was arrested and imprisoned for being a public drunkard. His business was then seized and taken over by the Mounties.

The building itself burned down a few years later in the Great Whitehorse Fire of 1905 — completely eradicating any earnings or savings Ernest had made during the entire endeavor.

Make Like a Bandit

By now, Friedrich was a somewhat wealthy man. While thousands of miners lost their wallets, backs, and lives — every one of them paid the toll to Fred’s business.

And he got out just in time.

Having nowhere in particular to go, he snuck back into his hometown way over in Germany. While there, he met and married a woman by the name of Elisabeth Christ (no relation to Jesus).

The newlyweds moved across the ocean back to big New York City. He got a job as a barber and hotel manager in a German-speaking neighborhood of the Bronx where his wife would be comfortable.

Shortly after in 1904 they had their first child, a girl. Wanting to raise her in the homeland, they returned to Germany hoping to start yet another life.

While there, he deposited his entire savings of around 8,000 Deutsche Marks — somewhere near $600,000 in today’s currency. Not bad for a poor sickly boy from Bavaria.

But Germany had not forgotten his draft-dodging ways.

Despite months of appeals and attempts of influence, he had to go. Yet another royal decree was issued forcing Friedrich and his family to leave Germany within a few weeks or be imprisoned.

And back to New York, they went.

The New Americans

Back in his old-new city, Friedrich and his wife got busy getting busy. They had two more sons over the next few years, Fred and John.

Friedrich opened up a barbershop in New York. Smack dab in the middle of Wall Street.

A little while later, he bought a large plot of real estate on Jamaica Avenue. His family moved in there while renting out several rooms on the spot.

At the same time, he gained employment as a manager of a large hotel chain nearby. While he probably had aspirations of continuing his land purchases, the world was changing.

WWI was just around the corner, and the anti-German sentiment was growing stronger than ever.

It was safer to maintain a small profile and a smaller fortune than to risk losing it all — especially since they were banned from returning to their homeland.

A few years later in 1918, Friedrich succumbed to a scary new sickness which came to be called the Spanish Flu — the last major pandemic to hit the world before COVID.

At the time of his death, he owned five vacant plots of land, a large house/boarding hotel, several stocks, 14 mortgages, and some cash savings.

His son Fred went on to continue his real estate aspirations.

Who was Friedrich?

Friedrich was a German illegal immigrant who liked to skirt the law whenever he could earn a buck.

He profited and possibly participated in illegal prostitution throughout his career.

He used a loophole to avoid conscription in the German Army.

Several times in his career, he made out with huge amounts of profits while everyone else around him suffered monetarily, or worse.

Now, if you think about a certain recent US president, can you see any sorts of similarities here?

Our young sickly German immigrant was none other than Friedrich Trump, the grandfather of former President Donald J. Trump Sr. (R-Florida). Friedrich’s son, Fred Trump made a fortune in housing and founded the Trump Organization, the family real estate empire.

Donald J. Trump Senior is the son of Fred Trump. The former president never knew his grandfather who died of Spanish Influenza in 1918. The Donald was born in 1946.

I suppose the apple doesn’t fall too far from the tree, even if it’s two generations later.

J.J. Pryor

Want more fun stories? Join Pryor Thoughts for free today!

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Trump

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Pass

- Blair, Gwenda (2000). The Trumps: Three Generations That Built an Empire. : Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978–0–7432–1079–9.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klondike_Gold_Rush

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monte_Cristo,_Washington

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pioneer_Square,_Seattle

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitehorse