January of 1917 was a tumultuous time, to say the least. America had not yet joined the war. Germany and its allies looked to be on a winning trajectory. The world was fraught with fear.

Over in the US, politics raged over whether or not to come to the assistance of the Allies. A lot of money was to be made in supplying the war effort by shipping ammunitions and material across the Atlantic.

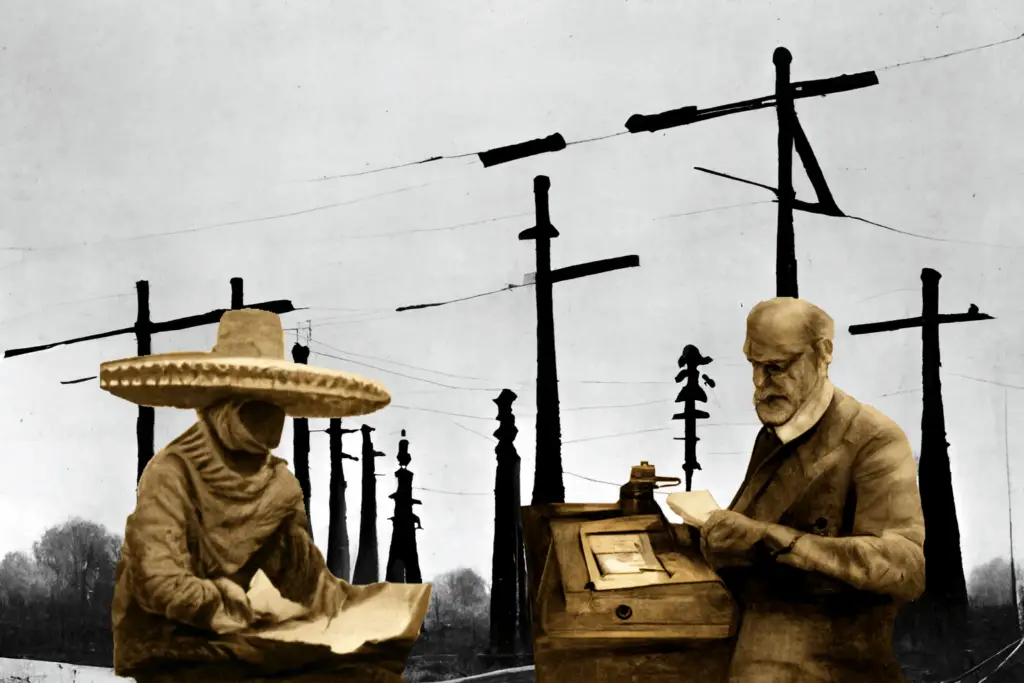

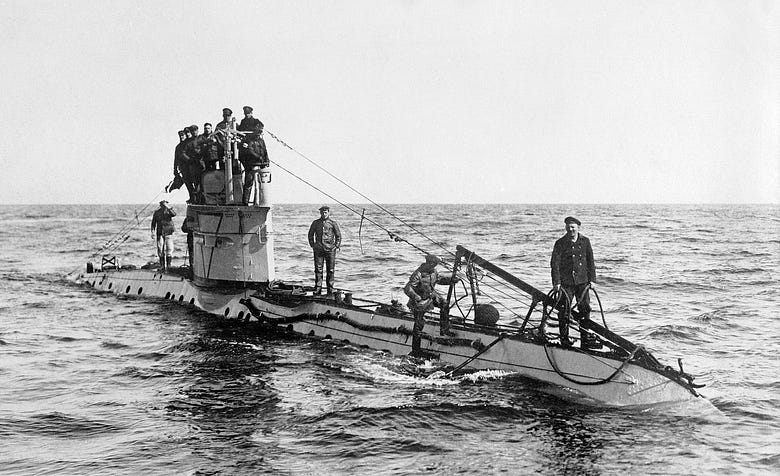

But there was one tiny speed bump — Germany’s U-boats. Vicious machines that stalked the ocean’s depths and were capable of taking down even the largest of ocean liners.

And they did just that in 1915, sinking one of the UK’s largest ships, the RMS Lusitania. Nearly 1,200 innocent civilians died in this shocking attack — including almost 200 Americans.

It was the first major strike in turning public opinion in the US against Germany.

But that didn’t completely occur until two years later after a strange gamble on a simple telegram.

Friendly Neighbors?

Mexico and the United States weren’t the happiest of neighbors in the 1910s.

There were several aspects to this:

- There was a civil war being raged in Mexico, with American politicians increasingly unsure of who to support

- Mexico was a potential supplier of arms to the Central Powers as they were still neutral

- A rogue paramilitary force being commanded by Pancho Villa was quite fond of raiding American villages and towns across the border

- Germany wanted Mexico to go to war with the US

These factors combined into several antagonistic incidents that heavily strained relations with the two countries. In 1914, America decided to start enforcing its arms embargo and occupied the area of Veracruz, even though it was considered illegal.

It took a peace conference in beautiful Niagara Falls to avert war that time, but the damage to the two countries was done.

Mexicans and Americans did not like each other.

Lurking Death Machines

The U-boats were a contentious war machine. They sometimes killed indiscriminately, not always able to properly identify their targets. They were dangerous for both the enemies and for the operators of these death traps.

Records show 373 U-boats were manufactured during WWI. Shockingly, at least 178 (48%) of them were destroyed and sunk by enemies through the conflict.

Not the best odds if you’re looking to set sail somewhere.

That ocean liner that was sunk before? It led to a very important declaration by the leaders of Germany to the United States.

A promise to stop targeting passenger ships and weaponless merchant liners. It was called the Sussex Pledge and it was abided by for the most part.

Until January of 1917, that is. That’s when Germany changed its mind after having manufactured hundreds of the sub-water death machines.

They felt reopening the policy of attacking anything in sight could easily allow them to overtake the UK’s dominance of the ocean. Win dominance of the UK, win the war.

Logical decision, poor outcome.

Control of the Seas

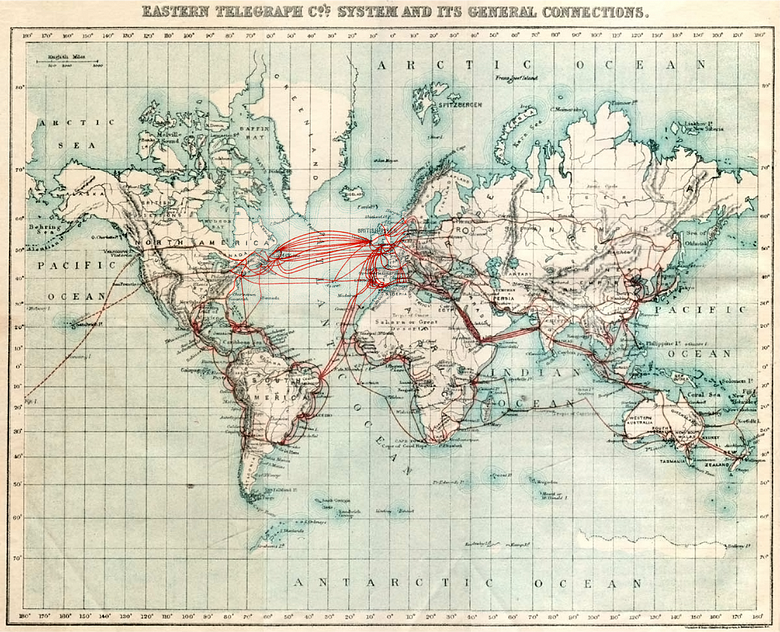

At the start of the war, the UK had a clear advantage in the sea. They controlled the waves, they controlled the commerce, and they controlled the communication cables to mainland Europe — which they proceeded to cut the ones running to Germany.

This presented a slight problem for the Central Powers, which still wanted to communicate with countries in the Western Hemisphere. To do so, they went through several indirect methods involving embassies of neutral or allied countries.

Most of these pathways, as ironic as it seemed, went through a control point in the UK itself.

And the UK had a secret — Room 40 — a part of British Intelligence. These cryptographic code busters knew the entire codebook of Germany at the time. Something the arrogance of German intellectuals refused to believe possible at the time.

And as arrogance usually has a way of interfering with proper planning, this time was no different.

Fire at Will

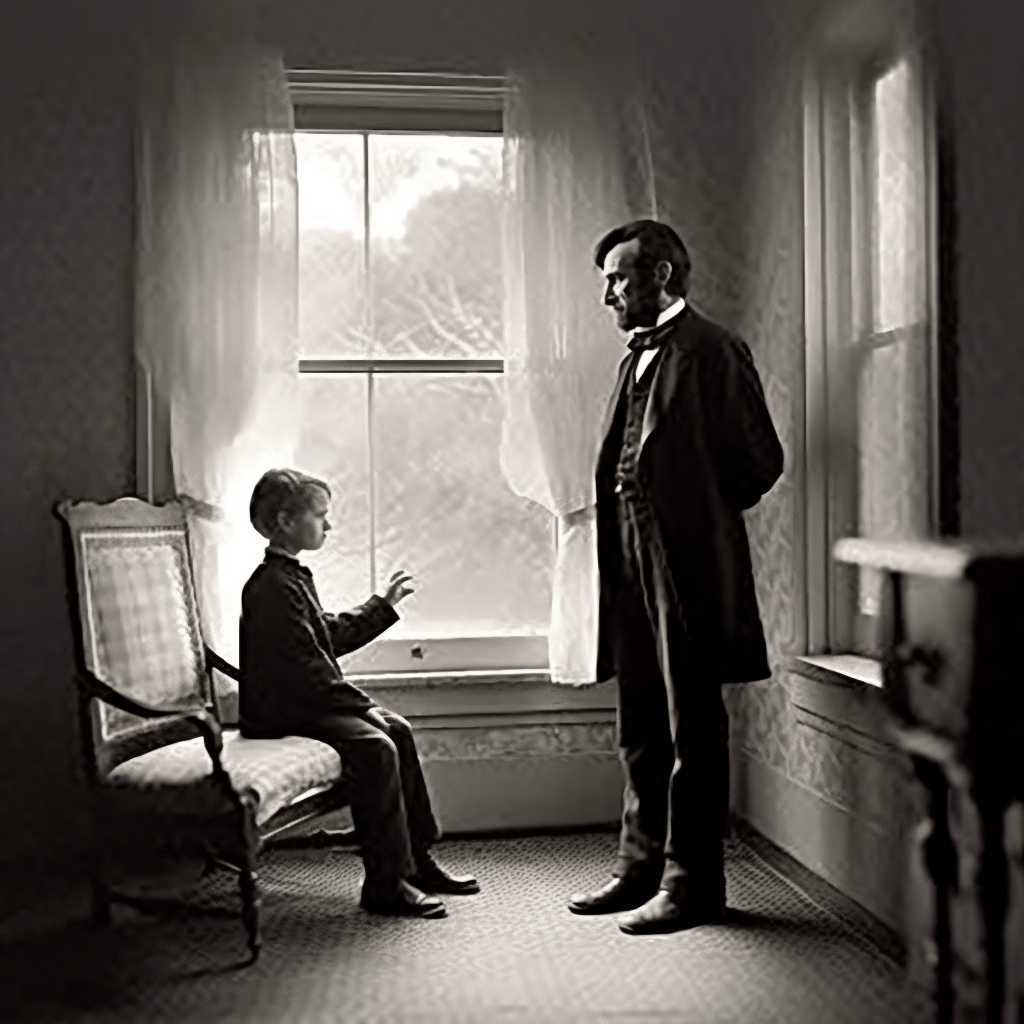

On January 31 in 1917, Germany declared the following day would mark the beginning of unrestricted naval warfare. Two weeks earlier, one of the country’s top civil servants, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a secret telegram to Mexico.

The American embassy, with whom he was transferring the message to Mexico, allowed him to pass a coded transcript to Mexico.

It was of course transcribed, decoded, and analyzed by Room 40.

The message contained a shocking offer:

Go to war with the US and we’ll give you all the gold you could need and let you take back Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona — the lost Mexican states from the past.

This bombshell of a telegram was a huge boon to Britain at the time. At last, they had a reason to bring America into the war and swing back the tide of Allies.

They only had two slight problems.

- The US didn’t know all of their messages were being intercepted by British intelligence

- Germany didn’t know British Intelligence could decode all of their messages and transmissions in war

Precarious.

Which code is THE code?

Convinced of the sheer alarming power of the telegram, British intelligence spent ample resources in February trying to devise a solution to their conundrum, without letting America or Germany know their secrets.

The sweet spot landed with a British spy who worked in the telegraphic office in Mexico. He convinced an employee there to hand over a different copy of the telegram — one that used different encryption.

Luckily for the British, this message used one of the older German codes — a code the Central Powers knew was already decoded by the British.

Regardless of this fortunate message, less than a few weeks later on March 3, Zimmerman admitted to an American journalist the content of the message.

“I cannot deny it. It is true.” — Zimmerman

The cat was out of the bag and Britain no longer had to convince anyone of the source and authenticity of the telegram.

Reactions

Sure enough, Germany began their campaign of unrestricted warfare on February 1st, sinking two merchant ships that month.

The Mexican leadership held a commission to consider the proposal from Germany, but they felt they couldn’t trust the proposal nor could they defeat the US militarily — and quickly abandoned the idea.

The US, on the other hand, was now pissed off. On April 6 of that year, Congress finally voted to declare war on Germany.

“A war to end all wars” — they mistakenly thought at the time.

Mexico remained neutral throughout the rest of WWI, which was likely the best scenario the US could have hoped for. Being undistracted with a border war to the south, they were able to focus their maximum efforts on aiding the allies with equipment, ammunition, and eventually soldiers.

The fateful telegram is now known as the Zimmerman Telegram and is widely thought to be the straw that broke the camel’s back of American anti-war opinion.

The rest is history.

Want more fun stories? Join Pryor Thoughts for free today!